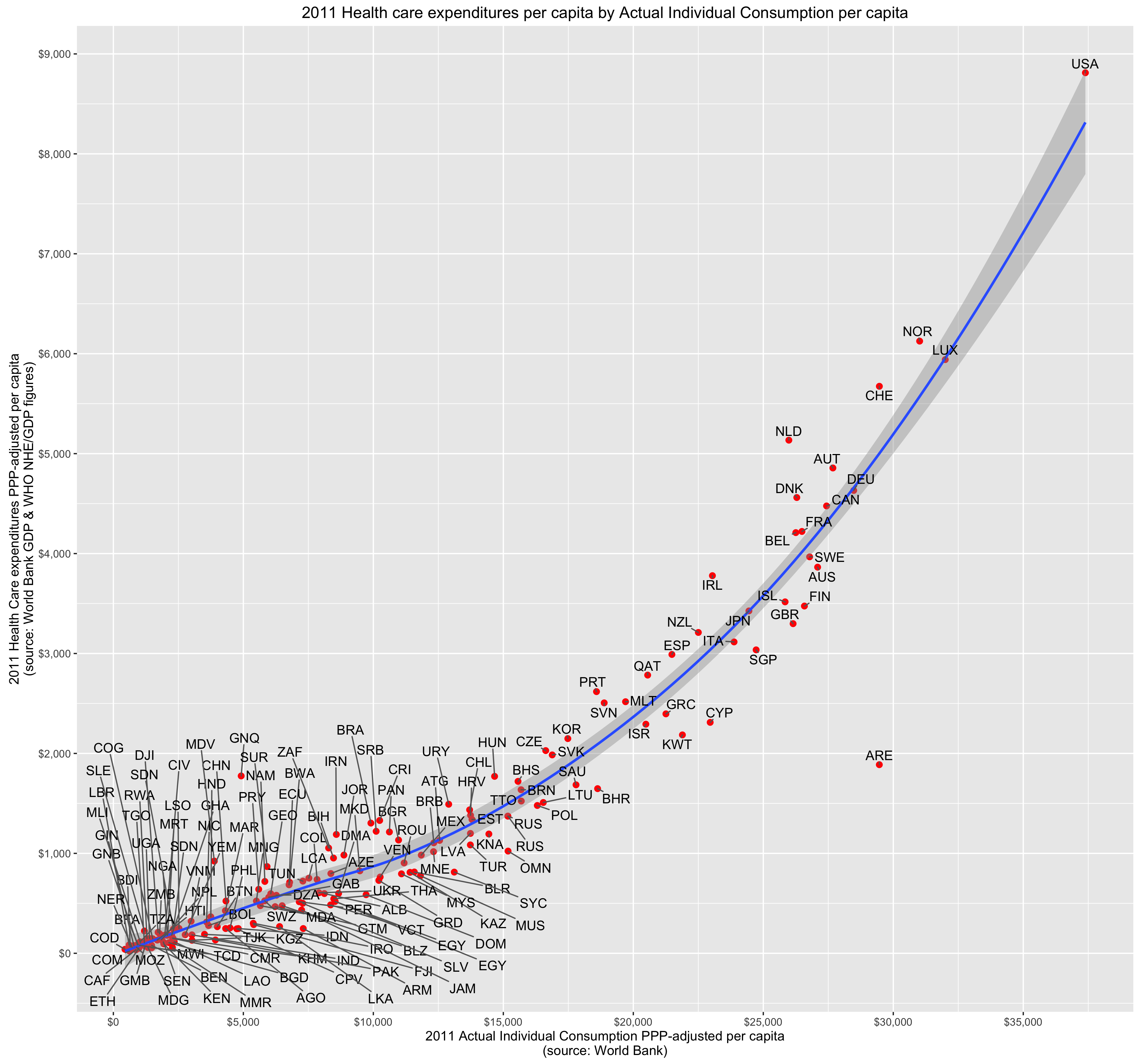

When properly analyzed with better data and closer attention to detail, it becomes quite clear that US healthcare spending is not astronomically high for a country of its wealth. Below I will layout these arguments in much greater detail and provide data, plots, and some statistical analysis to prove my point.

Using Actual Individual Consumption (AIC) we can explain the vast majority of healthcare expenditure differences between countries in any given year and the evolution of healthcare expenditure increases across more than 40 years!

Total per capita health care spending increases as wealth increases because people actually demand more goods and services (volume) per capita and because it is relatively labor intensive sector that does not enjoy the productivity gains found in some other sectors of the economy, i.e., overall costs increase through both volume and price together (volume * price).

…

Now, to be clear, my position is not that we ought to be spending as much as we spend. My position is that the issues we face are very similar to the issues faced in Europe and other prosperous countries (and are generally similar to patterns many decades earlier). They are largely differences in degree, not kind. Our large apparent cost differences mostly originate from our significantly higher material standard of living. The long term increases found in the United States and other developed countries are generally a product of ever increasing material living conditions and varying levels of productivity in different economic sectors (healthcare being labor intensive and relatively high skilled at that).

There is much less low hanging fruit than people imagine, even less so at a political level when people can actually express their preferences at the voting booth and various other interest groups (providers, hospitals, etc) can influence the process.