Source: The Real Class War – American Affairs Journal, By Julius Krein

The socioeconomic divide that will determine the future of politics, particularly in the United States, is not between the top 30 percent or 10 percent and the rest, nor even between the 1 percent and the 99 percent. The real class war is between the 0.1 percent and (at most) the 10 percent—or, more precisely, between elites primarily dependent on capital gains and those primarily dependent on professional labor.

…

While the top 5 or 10 percent may not deserve public sympathy, their underperformance relative to the top 0.1 percent will be more politically significant than the hollowing out of the working or lower-middle classes. Unlike the working class, the professional managerial class is still capable of, and required for, wielding political power.

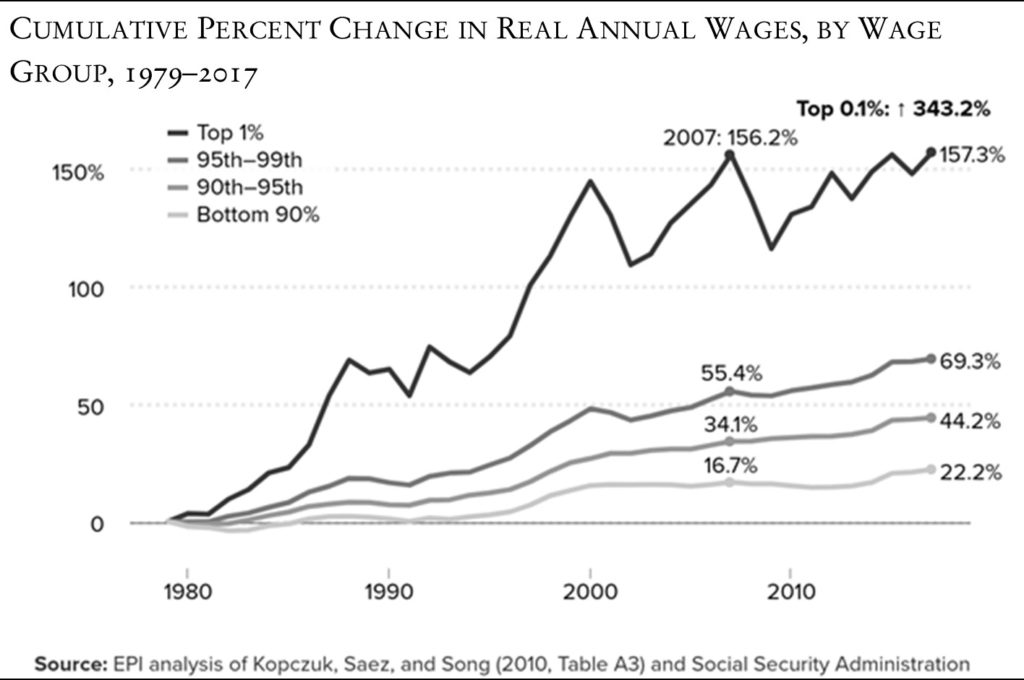

Members of the top 5 or 10 percent have done better than the middle and working classes in recent decades, but this masks their dramatic underperformance relative to the top 1 percent (and especially the top 0.1 percent).

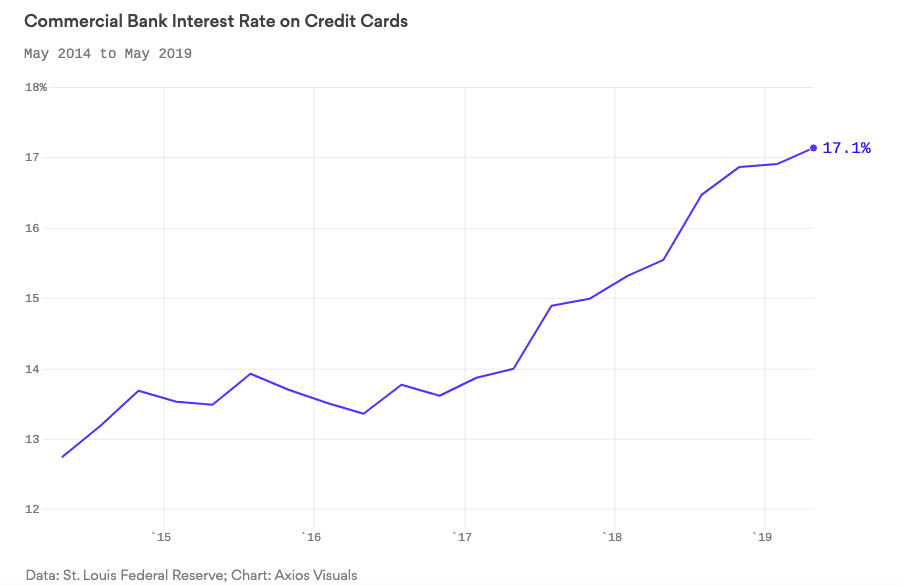

the costs of maintaining elite status—and passing it on to one’s children—have risen disproportionately for the top 5 or 10 percent. The ongoing decline of the middle and working classes may have reinforced the top 10 percent’s sense of elite status, but it also means that any backsliding would be catastrophic. These pressures have converged in two key areas in particular: real estate and education.

…

This underappreciated reality at least partially explains one of the apparent puzzles of American politics in recent years: namely, that members of the elite often seem far more radical than the working class, both in their candidate choices and overall outlook. … Many of the most aggressive proposals associated with the Left—such as student loan forgiveness and “free college”—are targeted at the top 30 percent, if not higher. Even Medicare for All could potentially benefit households earning between $100,000 and $200,000 the most; cohorts below that are already subsidized.

The purposelessness of many professional careers in the capital accumulation economy starkly contrasts with the growing number of unaddressed needs in the public sector. The legions of finance drones making utterly pointless discounted cash flow models could be far better employed designing a serious industrial policy. The engineers currently laboring over algorithms to make social media more addictive should be funded to focus on more productive technological advances. All the effort now devoted to coming up with new pricing strategies for old drugs could be directed at real medical problems, like increasing resistance to antibiotics. The vast resources invested in unprofitable ride-hailing apps and real estate arbitrage could have been used to solve America’s ever-increasing public infrastructure and housing challenges.