The whistleblower who leaked the drone papers believes the public is entitled to know how people are placed on kill lists and assassinated on orders from the president.

Drones are a tool, not a policy. The policy is assassination.

While many of the documents provided to The Intercept contain explicit internal recommendations for improving unconventional U.S. warfare, the source said that what’s implicit is even more significant. The mentality reflected in the documents on the assassination programs is: “This process can work. We can work out the kinks. We can excuse the mistakes. And eventually we will get it down to the point where we don’t have to continuously come back … and explain why a bunch of innocent people got killed.”

The architects of what amounts to a global assassination campaign do not appear concerned with either its enduring impact or its moral implications.

The costs to intelligence gathering when suspected terrorists are killed rather than captured are outlined in the slides pertaining to Yemen and Somalia, which are part of a 2013 study conducted by a Pentagon entity, the Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) Task Force.

Intelligence community documents obtained by The Intercept, detailing the purpose and achievements of the Haymaker campaign, indicate that the American forces involved in the operations had, at least on paper, all of the components they needed to succeed. … Despite all these advantages, the military’s own analysis demonstrates that the Haymaker campaign was in many respects a failure. The vast majority of those killed in airstrikes were not the direct targets. Nor did the campaign succeed in significantly degrading al Qaeda’s operations in the region.

With JSOC and the CIA running a new drone war in Iraq and Syria, much of Haymaker’s strategic legacy lives on. Such campaigns, with their tenuous strategic impacts and significant death tolls, should serve as a reminder of the dangers fallible lethal systems pose

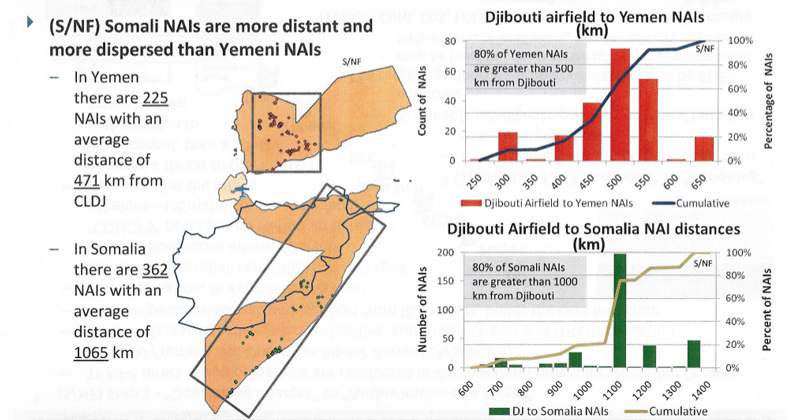

The Obama administration has portrayed drones as an effective and efficient weapon in the ongoing war with al Qaeda and other radical groups. Yet classified Pentagon documents obtained by The Intercept reveal that the U.S. military has faced “critical shortfalls” in the technology and intelligence it uses to find and kill suspected terrorists in Yemen and Somalia.

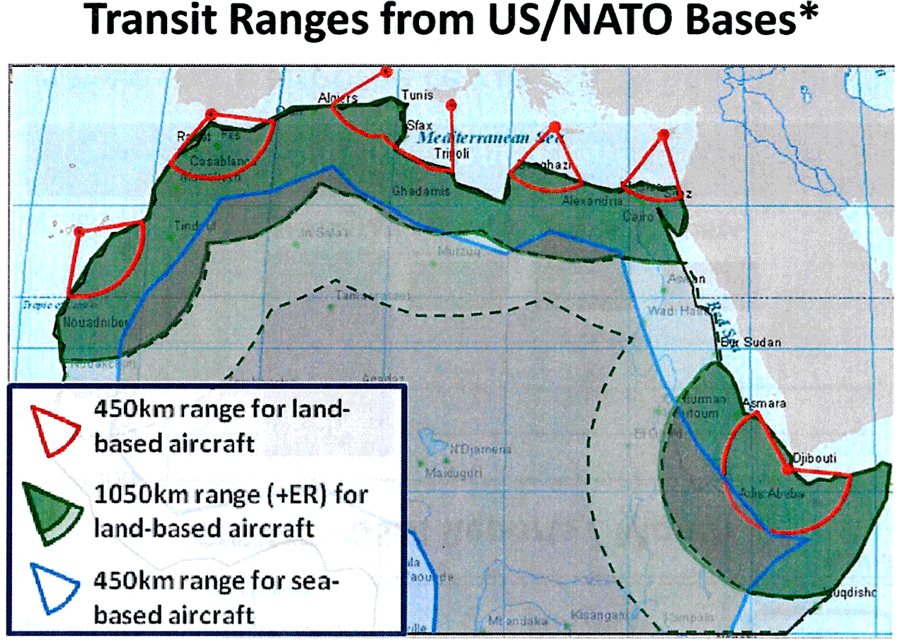

One of the most glaring problems identified in the ISR study was the U.S. military’s inability to carry out full-time surveillance of its targets in the Horn of Africa and Yemen. Behind this problem lies the “tyranny of distance” — a reference to the great lengths that aircraft must fly to their targets from the main U.S. air base in Djibouti, the small East African nation that borders Somalia and sits just across the Gulf of Aden from Yemen.

The documents state bluntly that SIGINT is an inferior form of intelligence. Yet signals accounted for more than half the intelligence collected on targets, with much of it coming from foreign partners. The rest originated with human intelligence, primarily obtained by the CIA.

The U.S. military has, since 9/11, engaged in a largely covert effort to extend its footprint across [Africa] with a network of mostly small and mostly low-profile camps. Some serve as staging areas for quick-reaction forces or bare-boned outposts where special ops teams can advise local proxies; some can accommodate large cargo planes, others only small surveillance aircraft. … These facilities allow U.S. forces to surveil and operate on larger and larger swaths of the continent — and, increasingly, to strike targets with drones and manned aircraft.

Source: The Assassination Complex