The president in conversation with MIT’s Joi Ito and WIRED editor-in-chief Scott Dadich.

[Obama:] Joi made a very elegant point, which is, what are the values that we’re going to embed in the cars? There are gonna be a bunch of choices that you have to make, the classic problem being: If the car is driving, you can swerve to avoid hitting a pedestrian, but then you might hit a wall and kill yourself. It’s a moral decision, and who’s setting up those rules?

[Obama:] Part of what makes us human are the kinks. They’re the mutations, the outliers, the flaws that create art or the new invention, right? We have to assume that if a system is perfect, then it’s static. And part of what makes us who we are, and part of what makes us alive, is that we’re dynamic and we’re surprised. One of the challenges that we’ll have to think about is, where and when is it appropriate for us to have things work exactly the way they’re supposed to, without surprises?

DADICH: But there are certainly some risks. We’ve heard from folks like Elon Musk and Nick Bostrom who are concerned about AI’s potential to outpace our ability to understand it. As we move forward, how do we think about those concerns as we try to protect not only ourselves but humanity at scale?

OBAMA: Let me start with what I think is the more immediate concern—it’s a solvable problem in this category of specialized AI, and we have to be mindful of it. If you’ve got a computer that can play Go, a pretty complicated game with a lot of variations, then developing an algorithm that lets you maximize profits on the New York Stock Exchange is probably within sight. And if one person or organization got there first, they could bring down the stock market pretty quickly, or at least they could raise questions about the integrity of the financial markets.

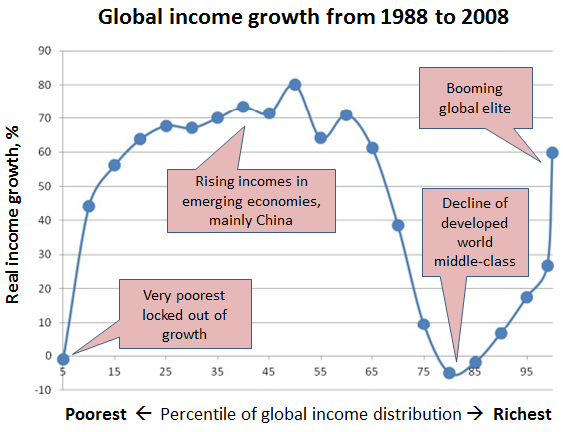

[Obama:] most people aren’t spending a lot of time right now worrying about singularity—they are worrying about “Well, is my job going to be replaced by a machine?” … if we are going to successfully manage this transition, we are going to have to have a societal conversation about how we manage this. … The social compact has to accommodate these new technologies, and our economic models have to accommodate them.

[Obama:] As a consequence, we have to make some tougher decisions. We underpay teachers, despite the fact that it’s a really hard job and a really hard thing for a computer to do well. So for us to reexamine what we value, what we are collectively willing to pay for—whether it’s teachers, nurses, caregivers, moms or dads who stay at home, artists, all the things that are incredibly valuable to us right now but don’t rank high on the pay totem pole—that’s a conversation we need to begin to have.

Source: Barack Obama on Artificial Intelligence, Autonomous Cars, and the Future of Humanity | WIRED