Source: America’s Monopoly Crisis Hits the Military | The American Conservative, by Matt Stoller and Lucas Kunce

the destruction of America’s once vibrant military and commercial industrial capacity in many sectors has become the single biggest unacknowledged threat to our national security. Because of public policies focused on finance instead of production, the United States increasingly cannot produce or maintain vital systems upon which our economy, our military, and our allies rely.

As part of his case for higher budgets, Mattis told Congress that “our military remains capable, but our competitive edge has eroded in every domain of warfare—air, land, sea, space, and cyber.” In some cases, our competitive edge has not just been eroded, but is at risk of being—or already is—surpassed. … And yet, the U.S. military budget, even at stalled levels, is still larger than the next nine countries’ budgets combined. So there’s a second natural follow-up question: is the defense budget the primary reason our military advantage is slipping away, or is it something deeper?

“The national ability to produce is a national treasure. If you can’t produce you won’t consume, and you can’t defend yourself.”

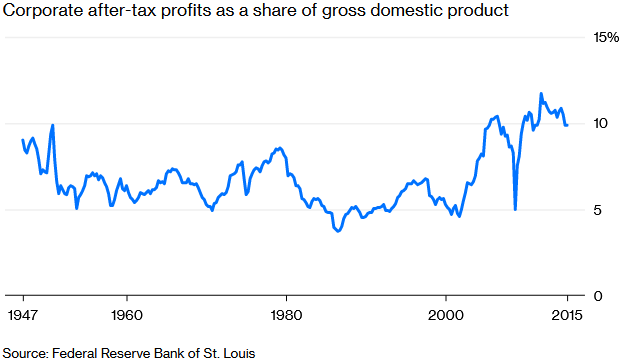

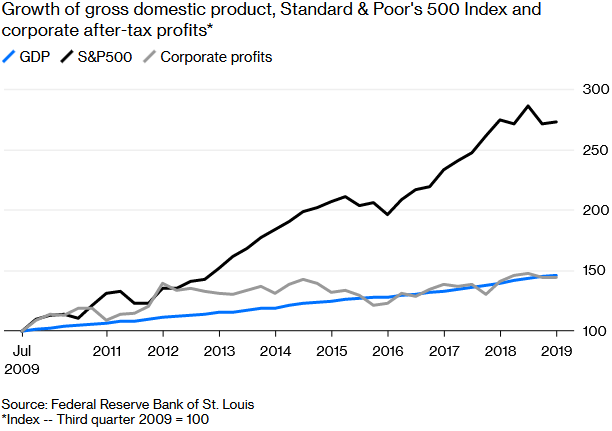

First, in the 1980s and 1990s, Wall Street financiers focused on short-term profits, market power, and executive pay-outs over core competencies like research and production, often rolling an industry up into a monopoly producer. Then, in the 2000s, they offshored production to the lowest cost producer.

…

When Wall Street targeted the commercial industrial base in the 1990s, the same financial trends shifted the defense industry. … financial pressure led to a change in focus for many in the defense industry—from technological engineering to balance sheet engineering. The result is that some of the biggest names in the industry have never created any defense product. Instead of innovating new technology to support our national security, they innovate new ways of creating monopolies to take advantage of it. … Fleecing the Defense Department is big business. … It is no wonder our military capacities are ebbing, despite the large budget outlays—the money isn’t going to defense.

The United States has, for instance, lost much of its fasteners and casting industries, which are key inputs to virtually every industrial product. It has lost much of its capacity in grain oriented flat-rolled electrical steel, a specialized metal required for highly efficient electrical motors. Aluminum that goes into American aircraft carriers now often comes from China.

…

In September 2018, the Department of Defense released findings of its analysis into its supply chain. … The report listed dozens of militarily significant items and inputs with only one or two domestic producers, or even none at all. .. Mortar tubes, for example, are made on just one production line, and some Marine aircraft parts are made by just one company—one which recently filed for bankruptcy.

…

the seldom-discussed background to our dependence on China for rare earths is that, just like with telecom equipment, the United States used to be the world leader in the industry until the financial sector shipped the whole thing to China. … China has a near-complete monopoly on rare earth elements, and the U.S. military, according to U.S. government studies, is now 100 percent reliant upon China for the resources to produce its advanced weapon systems.

[Representative Carol Shea-Porter] recounted a CEO once telling her, in response to her concern about the outsourcing of defense industry parts, that he “[has] to answer to stockholders.” Who are these stockholders that CEOs are so compelled to answer to? Oftentimes, China.

…

China has systematically targeted U.S. greenfield investments, “technology goods (especially semiconductors), R&D networks, and advanced manufacturing.” … “China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) stock in the U.S. increased some 800% between 2009 and 2015,” she wrote. Then, from 2015 to 2017, “Chinese FDI in the U.S. …climbed nearly four-fold, reaching roughly $45.6 billion in 2016, up from just $12.8 billion in 2014.”

…

CEOs not being able to worry about national security because they have to answer to the Chinese should elevate the issue to the top of our national security discussion.

the problems—diminished innovation, marginal quality, higher prices, less redundancy, dependence on overseas supply chains, a lack of defense industry competition, and reduced investment in research and development—are not independent. They are the result of the financialization of industry and of monopoly.

…

We must begin once again to recognize that private industrial capacity is a vital national security asset … a public good and short-term actors on Wall Street have become a serious national security vulnerability.