Source: How America Ends / Moderate Republicans Can Save America | The Atlantic, by Yoni Appelbaum

Democracy depends on the consent of the losers.

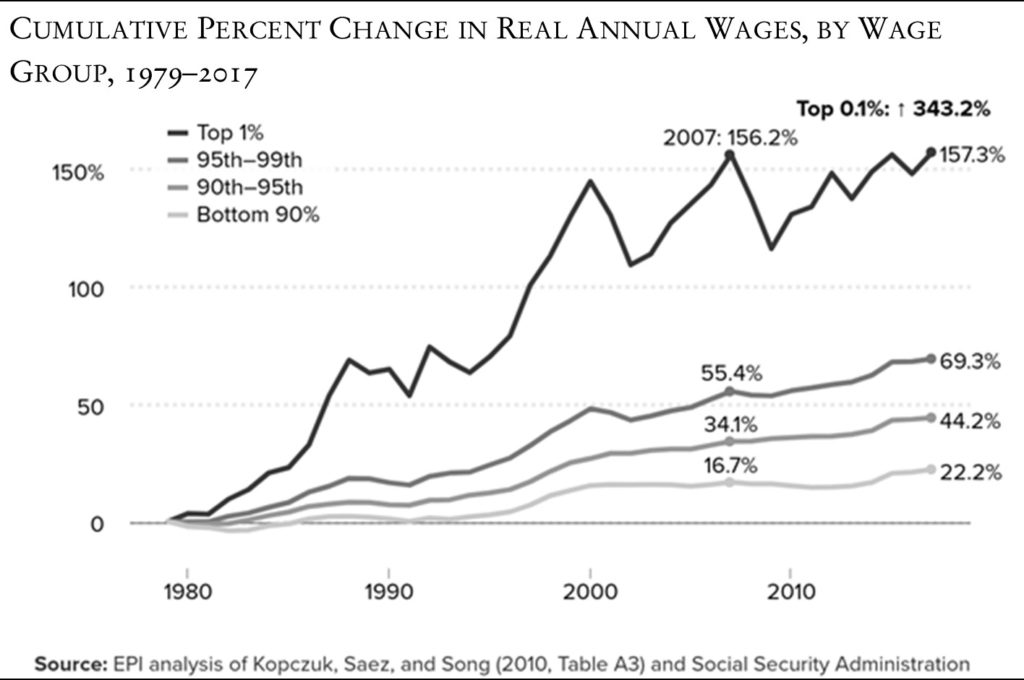

What has caused such rancor [in current U.S. politics]? … the biggest driver might be demographic change. … [The United State’s] historically dominant group is on its way to becoming a political minority—and its minority groups are asserting their co-equal rights and interests. If there are precedents for such a transition, they lie here in the United States, where white Englishmen initially predominated, and the boundaries of the dominant group have been under negotiation ever since. Yet those precedents are hardly comforting. Many of these renegotiations sparked political conflict or open violence

For a populist, Trump is remarkably unpopular. But no one should take comfort from that fact. The more he radicalizes his opponents against his agenda, the more he gives his own supporters to fear. The excesses of the left bind his supporters more tightly to him, even as the excesses of the right make it harder for the Republican Party to command majority support, validating the fear that the party is passing into eclipse, in a vicious cycle.

The right, and the country, can come back from this. Our history is rife with influential groups that, after discarding their commitment to democratic principles in an attempt to retain their grasp on power, lost their fight and then discovered they could thrive in the political order they had so feared. The Federalists passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, criminalizing criticism of their administration; Redemption-era Democrats stripped black voters of the franchise; and Progressive Republicans wrested municipal governance away from immigrant voters. Each rejected popular democracy out of fear that it would lose at the polls, and terror at what might then result. And in each case democracy eventually prevailed, without tragic effect on the losers. The American system works more often than it doesn’t.

…

The Democrats lost the presidential race in 1928—but won the next five, in one of the most dominant runs in American political history. The most effective way to protect the things they cherished, Democratic politicians belatedly discovered, wasn’t by locking immigrants out of the party, but by inviting them in.

Whether the American political system today can endure without fracturing further, Daniel Ziblatt’s research suggests, may depend on the choices the center-right now makes. If the center-right decides to accept some electoral defeats and then seeks to gain adherents via argumentation and attraction—and, crucially, eschews making racial heritage its organizing principle—then the GOP can remain vibrant. Its fissures will heal and its prospects will improve, as did those of the Democratic Party in the 1920s, after Wilson. Democracy will be maintained. But if the center-right, surveying demographic upheaval and finding the prospect of electoral losses intolerable, casts its lot with Trumpism and a far right rooted in ethno-nationalism, then it is doomed to an ever smaller proportion of voters, and risks revisiting the ugliest chapters of our history.

…

The Republican Party faced a choice between these two competing visions in the last presidential election. The post-2012 report defined the GOP ideologically, urging its leaders to reach out to new groups, emphasize the values they had in common, and rebuild the party into an organization capable of winning a majority of the votes in a presidential race. Anton’s essay, by contrast, defined the party as the defender of “a people, a civilization” threatened by America’s growing diversity.

…

When Trump’s presidency comes to its end, the Republican Party will confront the same choice it faced before his rise, only even more urgently. In 2013, the party’s leaders saw the path that lay before them clearly, and urged Republicans to reach out to voters of diverse backgrounds whose own values matched the “ideals, philosophy and principles” of the GOP. Trumpism deprioritizes conservative ideas and principles in favor of ethno-nationalism.

The conservative strands of America’s political heritage—a bias in favor of continuity, a love for traditions and institutions, a healthy skepticism of sharp departures—provide the nation with a requisite ballast. America is at once a land of continual change and a nation of strong continuities. Each new wave of immigration to the United States has altered its culture, but the immigrants themselves have embraced and thus conserved many of its core traditions. … And all became more American.

…

If America’s white Judeo-Christian majority is gone, then some new majority is already emerging to take its place—some new, more capacious way of understanding what it is to belong to the American mainstream.

So strong is the attraction of the American idea that it infects even our dissidents. The suffragists at Seneca Falls, Martin Luther King Jr. on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, and Harvey Milk in front of San Francisco’s city hall all quoted the Declaration of Independence. The United States possesses a strong radical tradition, but its most successful social movements have generally adopted the language of conservatism, framing their calls for change as an expression of America’s founding ideals rather than as a rejection of them.

The stakes in this battle on the right are much higher than the next election. If Republican voters can’t be convinced that democratic elections will continue to offer them a viable path to victory, that they can thrive within a diversifying nation, and that even in defeat their basic rights will be protected, then Trumpism will extend long after Trump leaves office—and our democracy will suffer for it.