Source: Economists are rethinking the numbers on inequality | The Economist

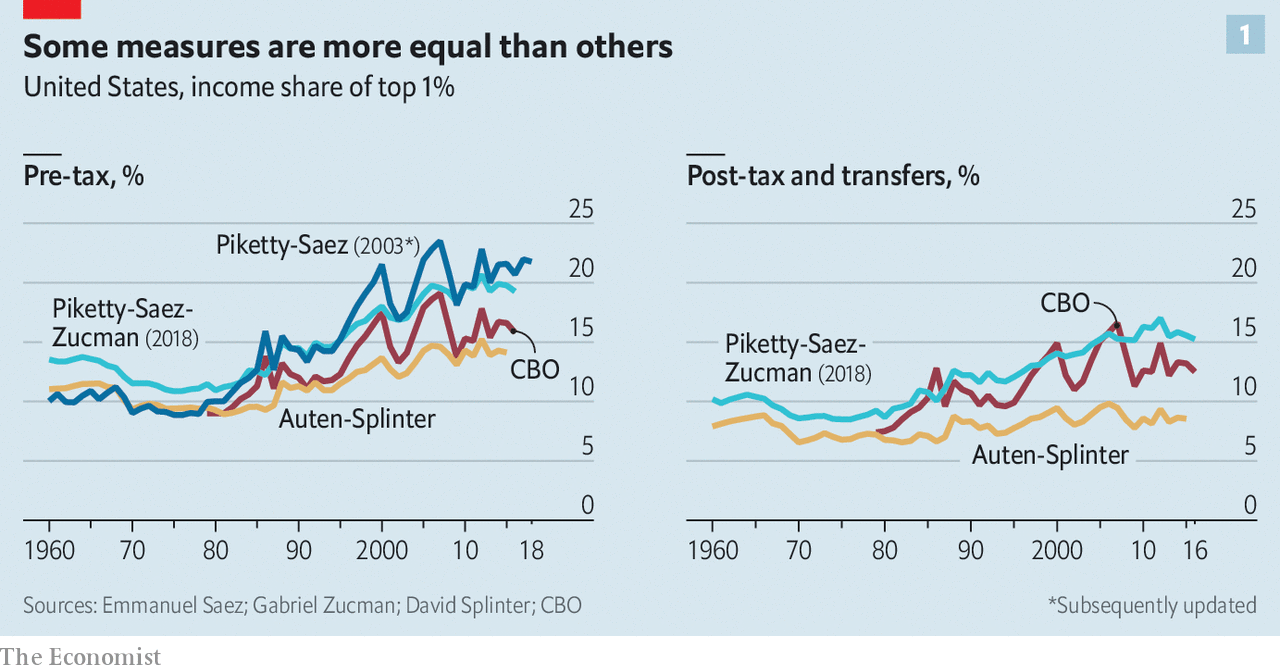

Yet just as ideas about inequality have completed their march from the academy to the frontlines of politics, researchers have begun to look again. And some are wondering whether inequality has in fact risen as much as claimed—or, by some measures, at all. It is fiendishly complicated to calculate how much people earn in a year or the value of the assets under their control, and thus a country’s level of income or wealth inequality.

…

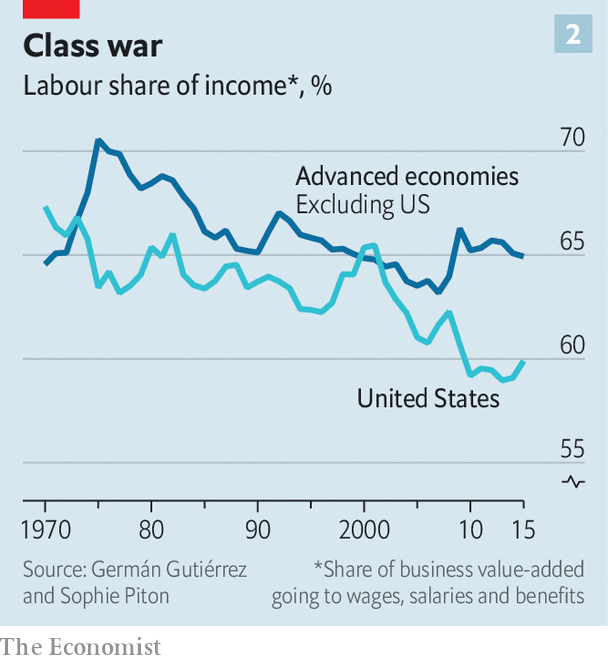

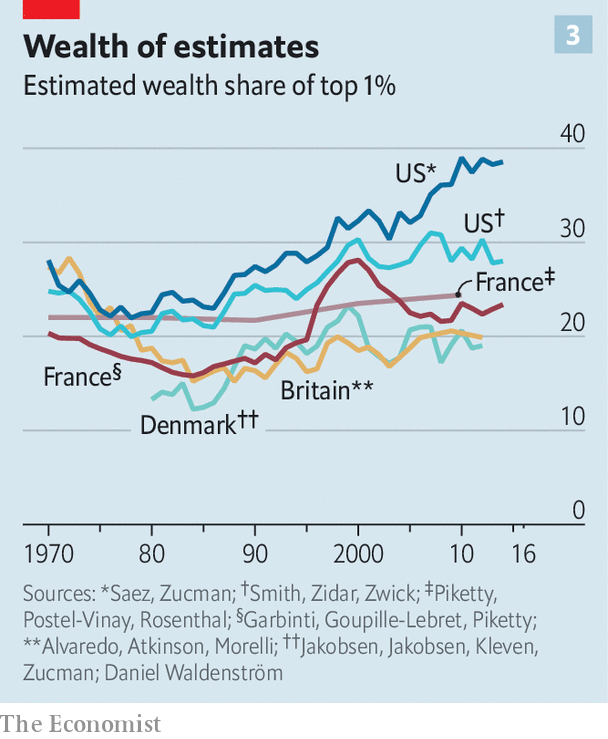

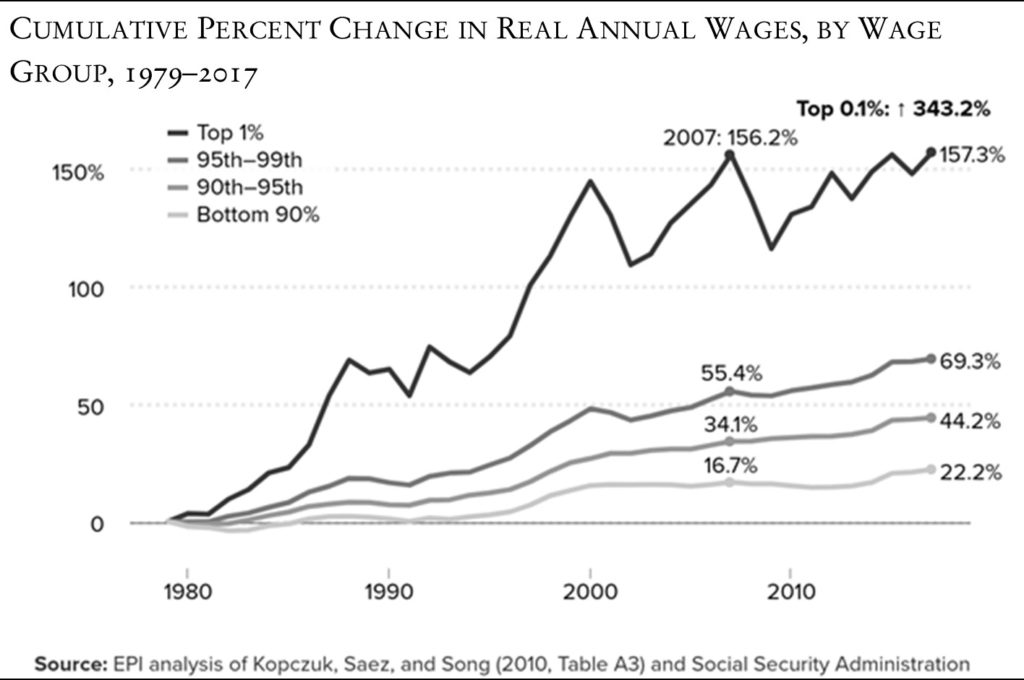

The conventional wisdom to have emerged from [recent wealth and income research] revolves around four main points. First, over a period of four to five decades the incomes of the top 1% have soared. Second, the incomes of middle-earners have stagnated. Third, wages have barely risen even though productivity has done so, meaning that an increasing share of GDP has gone to investors in the form of interest, dividends and capital gains, rather than to labour in the form of wages. Fourth, the rich have reinvested the fruits of their success, such that inequality of wealth (ie, the stock of assets less liabilities such as mortgage debt) has risen, too.Each argument has always had its doubters. But they have grown in number as a series of new papers have called the existing estimates of inequality into question.

Few dispute that wealth shares at the top have risen in America, nor that the increase is driven by fortunes at the very top, among people who really can be considered an elite. The question, instead, is by just how much. … Proposals for much heavier taxes on high earners, or a tax on net wealth, or the far more radical plans outlined in Mr Piketty’s latest book, are responses to a problem that is only partially understood.