The world can learn from how Norway treats its offenders

Source: Prisons: Too many prisons make bad people worse. There is a better way | The Economist

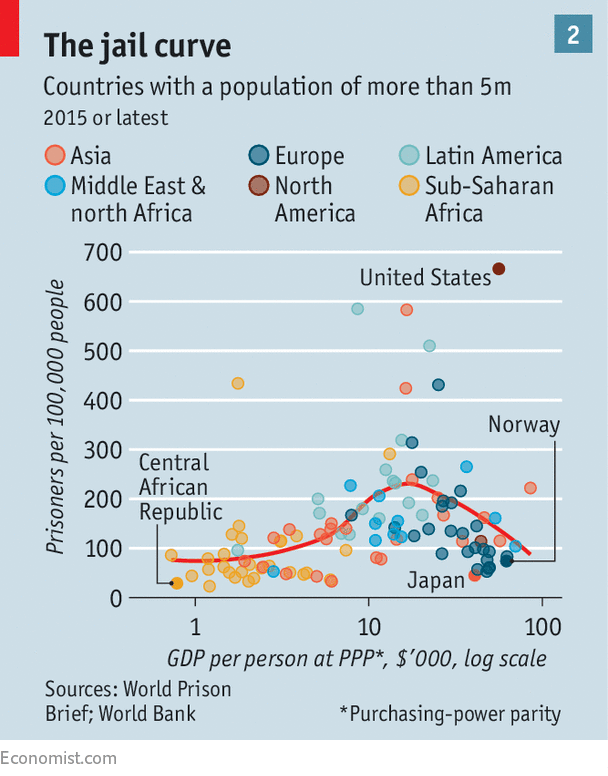

Norway has the lowest reoffending rate in Scandinavia: two years after release, only 20% of prisoners have been reconvicted. By contrast, a study of 29 American states found a recidivism rate nearly twice as high. This is despite the fact that Norway reserves prison for hard cases, who would normally be more likely to reoffend. Its incarceration rate, at 74 per 100,000 people, is about a tenth of America’s.

“Kentucky prisons were full of people we’re mad at, not people we’re afraid of,” says John Tilley, the secretary of justice in Kentucky.

for many people the aim of incarceration is to reduce the harm caused by criminals. Prisons can do this in three ways. First, they restrain: a thug behind bars cannot break into your house. Second, they deter: the prospect of being locked up makes potential wrongdoers think twice. Third, they reform: under state supervision, a criminal can be taught better habits.

On the first count, most prisons succeed, but at a cost.

…

To deter would-be criminals, what matters most is not the severity of the penalty but the certainty and swiftness with which it is imposed.

…

Even when the police are effective, criminals are often undeterred. They are typically impulsive and opportunistic, picking fights because they are angry and grabbing loot because it is visible. Which is why rehabilitation is so important: nearly all inmates will eventually be released, and it is far better for everyone if they do not go back to their old ways.