Source: Crony Beliefs | Melting Asphalt, by Kevin Simler

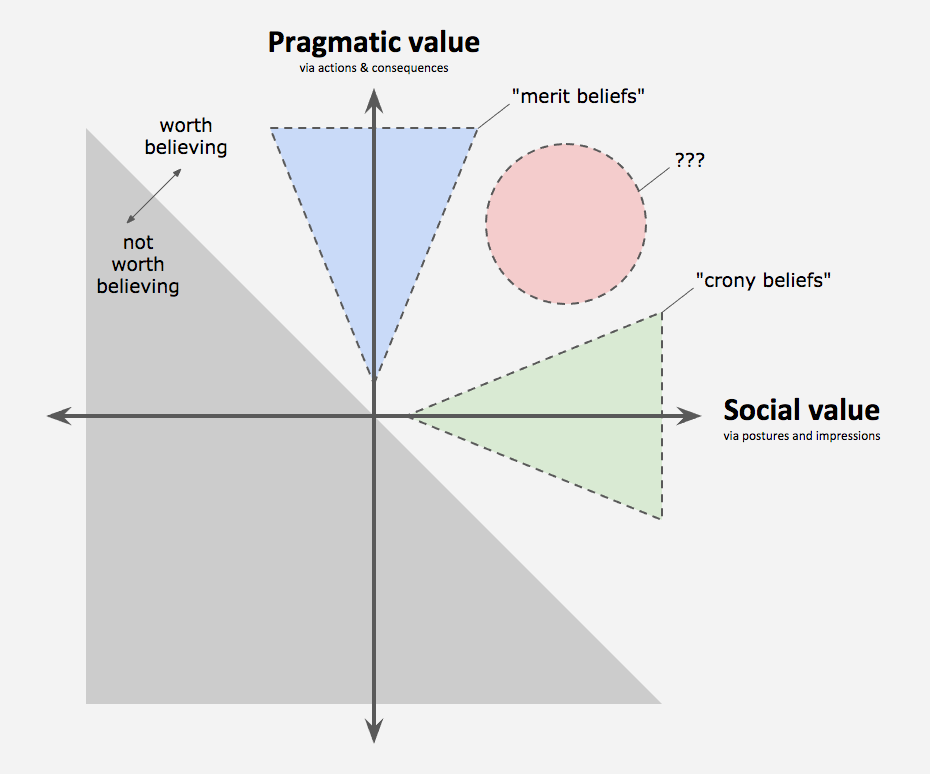

One of my main goals for writing this essay has been to introduce two new concepts — merit beliefs and crony beliefs — that I hope make it easier to talk and reason about epistemic problems. … it’s important to remember that merit beliefs aren’t necessarily true, nor are crony beliefs necessarily false. What distinguishes the two concepts is how we’re rewarded for them: via effective actions or via social impressions.

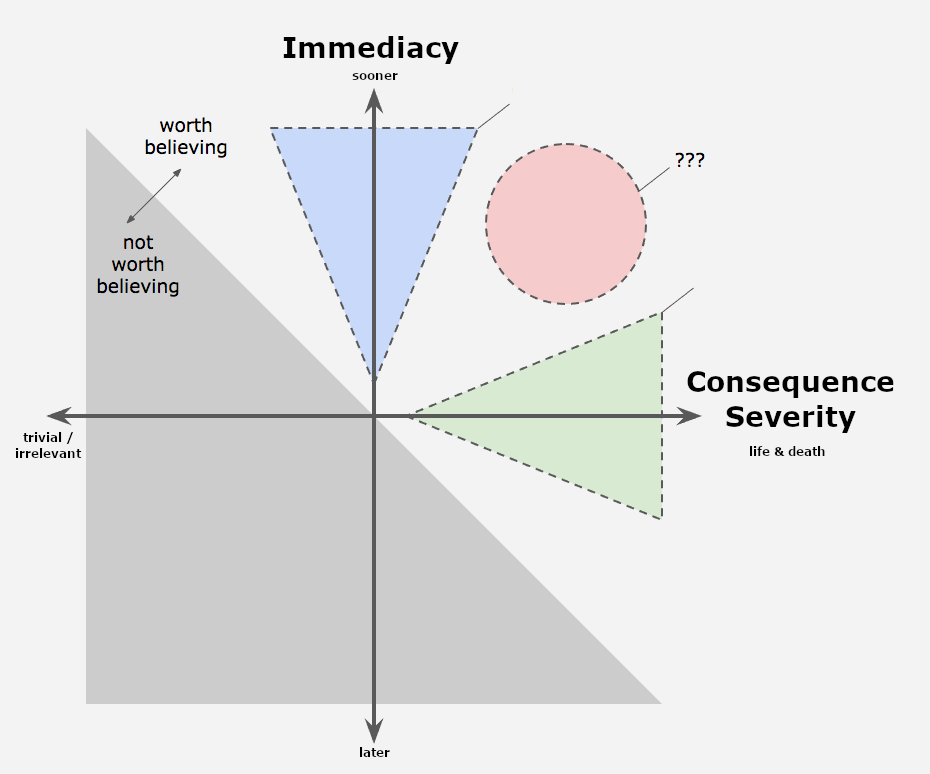

I found Kevin’s introduction of his concepts of merit and crony beliefs to be interesting and potentially useful, and I recommend reading the rest of his post. However, I complain that his “Identifying Crony Beliefs” and “J’accuse” sections sometimes confuse his merit/crony beliefs concept(s) with the immediacy and severity of potential consequences:

I disagree that “perhaps the biggest hallmark of epistemic cronyism is exhibiting strong emotions … These emotions have no business being within 1000ft of a meritocratic belief system”. For example, if I am with another person in a vehicle (as driver or passenger) approaching an intersection at speed, I probably have a strong opinion about whether or not my vehicle should be breaking to stop at the intersection or not; I will also have strong emotions if the other person is insisting that I am wrong. Similarly, I have no strong feelings about whether or not X, but the only conceivable value to believing that would be social, not practical, so it must be a crony belief.

Strong feelings are indicative of a belief’s high consequential value (positive or negative, social or practical), not of a belief’s social-ness.