Source: The 9.9 Percent Is the New American Aristocracy – The Atlantic, by Matthew Stewart

The meritocratic class has mastered the old trick of consolidating wealth and passing privilege along at the expense of other people’s children.

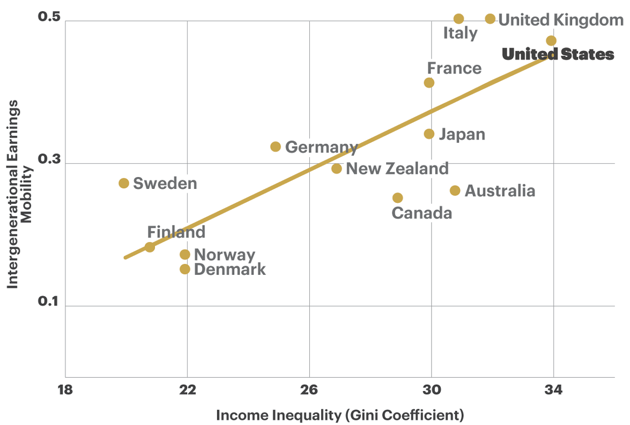

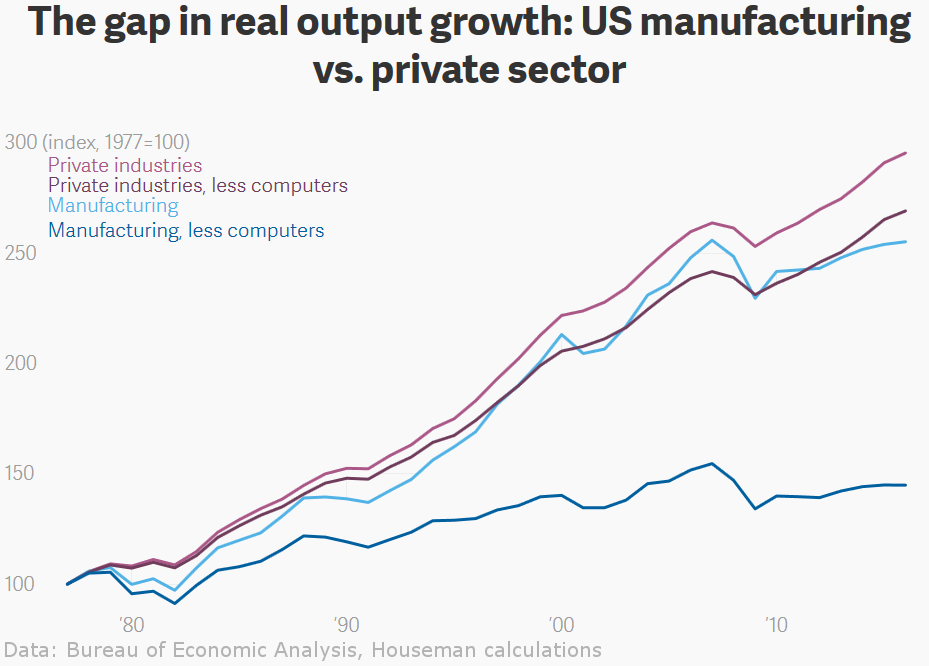

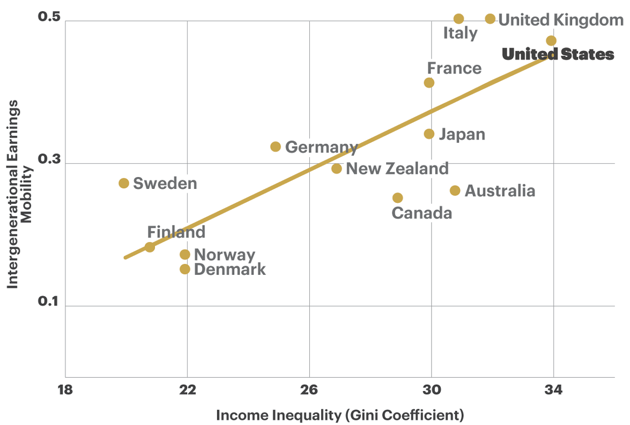

Contrary to popular myth, economic mobility in the land of opportunity is not high, and it’s going down.

The Gatsby Curve has managed to reproduce itself in social, physiological, and cultural capital. Put more accurately: There is only one curve, but it operates through a multiplicity of forms of wealth.

One of the hazards of life in the 9.9 percent is that our necks get stuck in the upward position. We gaze upon the 0.1 percent with a mixture of awe, envy, and eagerness to obey. As a consequence, we are missing the other big story of our time. We have left the 90 percent in the dust—and we’ve been quietly tossing down roadblocks behind us to make sure that they never catch up.

…

Money may be the measure of wealth, but it is far from the only form of it. Family, friends, social networks, personal health, culture, education, and even location are all ways of being rich, too. These nonfinancial forms of wealth, as it turns out, aren’t simply perks of membership in our aristocracy. They define us. We are the people of good family, good health, good schools, good neighborhoods, and good jobs. We may want to call ourselves the “5Gs” rather than the 9.9 percent.

…

The sociological data are not remotely ambiguous on any aspect of this growing divide. We 9.9 percenters live in safer neighborhoods, go to better schools, have shorter commutes, receive higher-quality health care, and, when circumstances require, serve time in better prisons. We also have more friends—the kind of friends who will introduce us to new clients or line up great internships for our kids. These special forms of wealth offer the further advantages that they are both harder to emulate and safer to brag about than high income alone. … We have figured out how to launder our money through higher virtues. Most important of all, we have learned how to pass all of these advantages down to our children.

It’s one of the delusions of our meritocratic class, however, to assume that if our actions are individually blameless, then the sum of our actions will be good for society. … Rising inequality decreases the number of suitably wealthy mates even as it increases the reward for finding one and the penalty for failing to do so. … The fact of the matter is that we have silently and collectively opted for inequality, and this is what inequality does. It turns marriage into a luxury good, and a stable family life into a privilege that the moneyed elite can pass along to their children. How do we think that’s going to work out?

We’re leaving the 90 percent and their offspring far behind in a cloud of debts and bad life choices that they somehow can’t stop themselves from making. We tend to overlook the fact that parenting is more expensive and motherhood more hazardous in the United States than in any other developed country, that campaigns against family planning and reproductive rights are an assault on the families of the bottom 90 percent, and that law-and-order politics serves to keep even more of them down. We prefer to interpret their relative poverty as vice: Why can’t they get their act together?

…

Rising inequality does not follow from a hidden law of economics, as the otherwise insightful Thomas Piketty suggested when he claimed that the historical rate of return on capital exceeds the historical rate of growth in the economy. Inequality necessarily entrenches itself through other, nonfinancial, intrinsically invidious forms of wealth and power. We use these other forms of capital to project our advantages into life itself. We look down from our higher virtues in the same way the English upper class looked down from its taller bodies, as if the distinction between superior and inferior were an artifact of nature.

Thanks to ambitious university administrators and the ever-expanding rankings machine at U.S. News & World Report, 50 colleges are now as selective as Princeton was in 1980, when I applied. The colleges seem to think that piling up rejections makes them special. In fact, it just means that they have collectively opted to deploy their massive, tax-subsidized endowments to replicate privilege rather than fulfill their duty to produce an educated public.

the fact is that degree holders earn so much more than the rest not primarily because they are better at their job, but because they mostly take different categories of jobs. … The exceptionalism of American compensation rates comes to an end in the kinds of work that do not require a college degree. You see, when educated people with excellent credentials band together to advance their collective interest, it’s all part of serving the public good by ensuring a high quality of service, establishing fair working conditions, and giving merit its due. That’s why we do it through “associations,” and with the assistance of fellow professionals wearing white shoes. When working-class people do it—through unions—it’s a violation of the sacred principles of the free market. It’s thuggish and anti-modern. Imagine if workers hired consultants and “compensation committees,” consisting of their peers at other companies, to recommend how much they should be paid. The result would be—well, we know what it would be, because that’s what CEOs do.

The income-tax system that so offended my grandfather has had the unintended effect of creating a highly discreet category of government expenditures. They’re called “tax breaks,” but it’s better to think of them as handouts that spare the government the inconvenience of collecting the money in the first place. … In total, federal tax expenditures exceeded $900 billion in 2013. That’s more than the cost of Medicare, more than the cost of Medicaid, more than the cost of all other federal safety-net programs put together. And—such is the beauty of the system—51 percent of those handouts went to the top quintile of earners, and 39 percent to the top decile.

…

The best thing about this program of reverse taxation, as far as the 9.9 percent are concerned, is that the bottom 90 percent haven’t got a clue. The working classes get riled up when they see someone at the grocery store flipping out their food stamps to buy a T-bone. They have no idea that a nice family on the other side of town is walking away with $100,000 for flipping their house.

With localized wealth comes localized political power, and not just of the kind that shows up in voting booths. Which brings us back to the depopulation paradox. Given the social and cultural capital that flows through wealthy neighborhoods, is it any wonder that we can defend our turf in the zoning wars? We have lots of ways to make that sound public-spirited. It’s all about saving the local environment, preserving the historic character of the neighborhood, and avoiding overcrowding. In reality, it’s about hoarding power and opportunity inside the walls of our own castles.

Human beings of the 9.9 percent variety also routinely conflate the stress of status competition with the stress of survival. No, failing to get your kid into Stanford is not a life-altering calamity. … And yet, even allowing for these all-too-human failures of cognition, the cries of anguish that echo across the soccer fields at the mere suggestion of unearned privilege are too persistent to ignore. Fact-challenged though they may be, they speak to a certain, deeper truth about life in the 9.9 percent. What they are really telling us is that being an aristocrat is not quite what it is cracked up to be. A strange truth about the Gatsby Curve is that even as it locks in our privileges, it doesn’t seem to make things all that much easier. … We have intuited one of the fundamental paradoxes of life on the Gatsby Curve: The greater the inequality, the less your money buys.

The source of the trouble, considered more deeply, is that we have traded rights for privileges. We’re willing to strip everyone, including ourselves, of the universal right to a good education, adequate health care, adequate representation in the workplace, genuinely equal opportunities, because we think we can win the game. But who, really, in the end, is going to win this slippery game of escalating privileges?

The raging polarization of American political life is not the consequence of bad manners or a lack of mutual understanding. It is just the loud aftermath of escalating inequality. It could not have happened without the 0.1 percent … But that is not to let the 9.9 percent off the hook. We may not be the ones funding the race-baiting, but we are the ones hoarding the opportunities of daily life. We are the staff that runs the machine that funnels resources from the 90 percent to the 0.1 percent. We’ve been happy to take our cut of the spoils. We’ve looked on with smug disdain as our labors have brought forth a population prone to resentment and ripe for manipulation. We should be prepared to embrace the consequences.

The first important thing to know about these consequences is the most obvious: Resentment is a solution to nothing. It isn’t a program of reform. It isn’t “populism.” It is an affliction of democracy, not an instance of it. The politics of resentment is a means of increasing inequality, not reducing it.

…

The second thing to know is that we are next in line for the chopping block. As the population of the resentful expands, the circle of joy near the top gets smaller. The people riding popular rage to glory eventually realize that we are less useful to them as servants of the economic machine than we are as model enemies of the people.

The American idea has always been a guide star, not a policy program, much less a reality. The rights of human beings never have been and never could be permanently established in a handful of phrases or old declarations. They are always rushing to catch up to the world that we inhabit. In our world, now, we need to understand that access to the means of sustaining good health, the opportunity to learn from the wisdom accumulated in our culture, and the expectation that one may do so in a decent home and neighborhood are not privileges to be reserved for the few who have learned to game the system. They are rights that follow from the same source as those that an earlier generation called life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Yes, the kind of change that really matters is going to require action from the federal government. That which creates monopoly power can also destroy it; that which allows money into politics can also take it out; that which has transferred power from labor to capital can transfer it back. Change also needs to happen at the state and local levels. How else are we going to open up our neighborhoods and restore the public character of education?

It’s going to take something from each of us, too, and perhaps especially from those who happen to be the momentary winners of this cycle in the game. We need to peel our eyes away from the mirror of our own success and think about what we can do in our everyday lives for the people who aren’t our neighbors. We should be fighting for opportunities for other people’s children as if the future of our own children depended on it. It probably does.