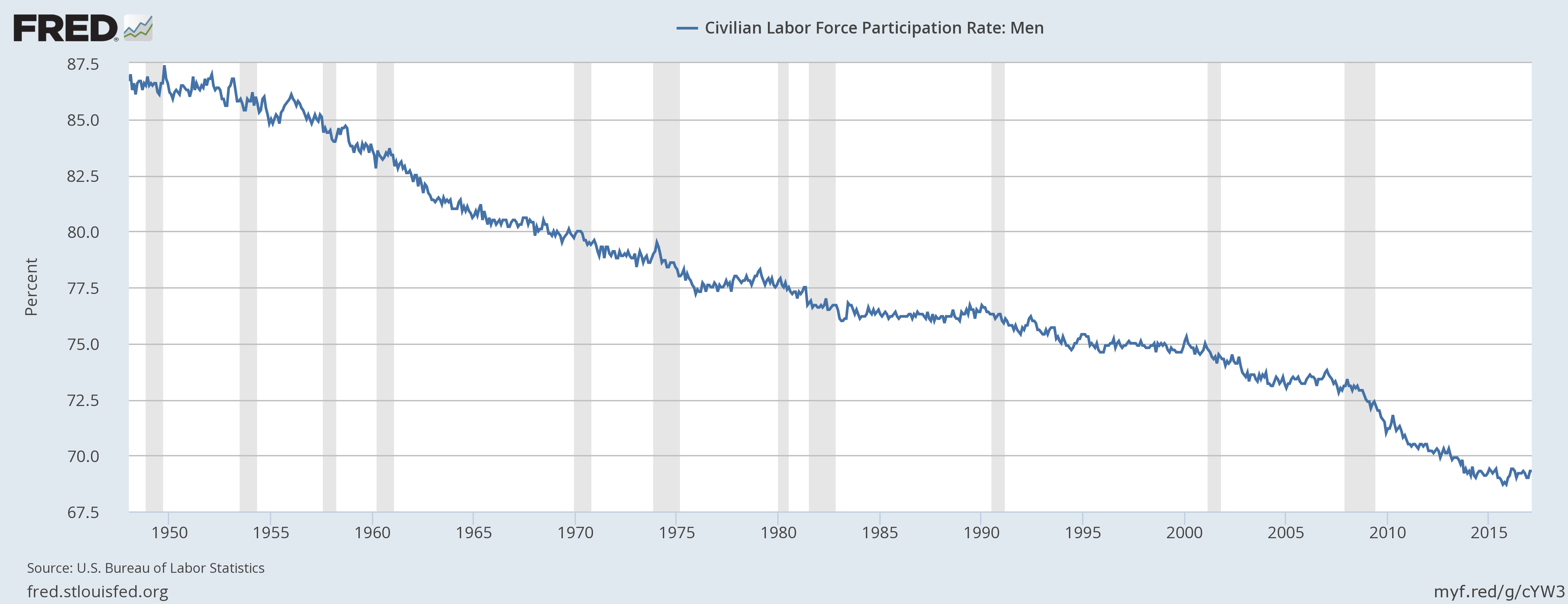

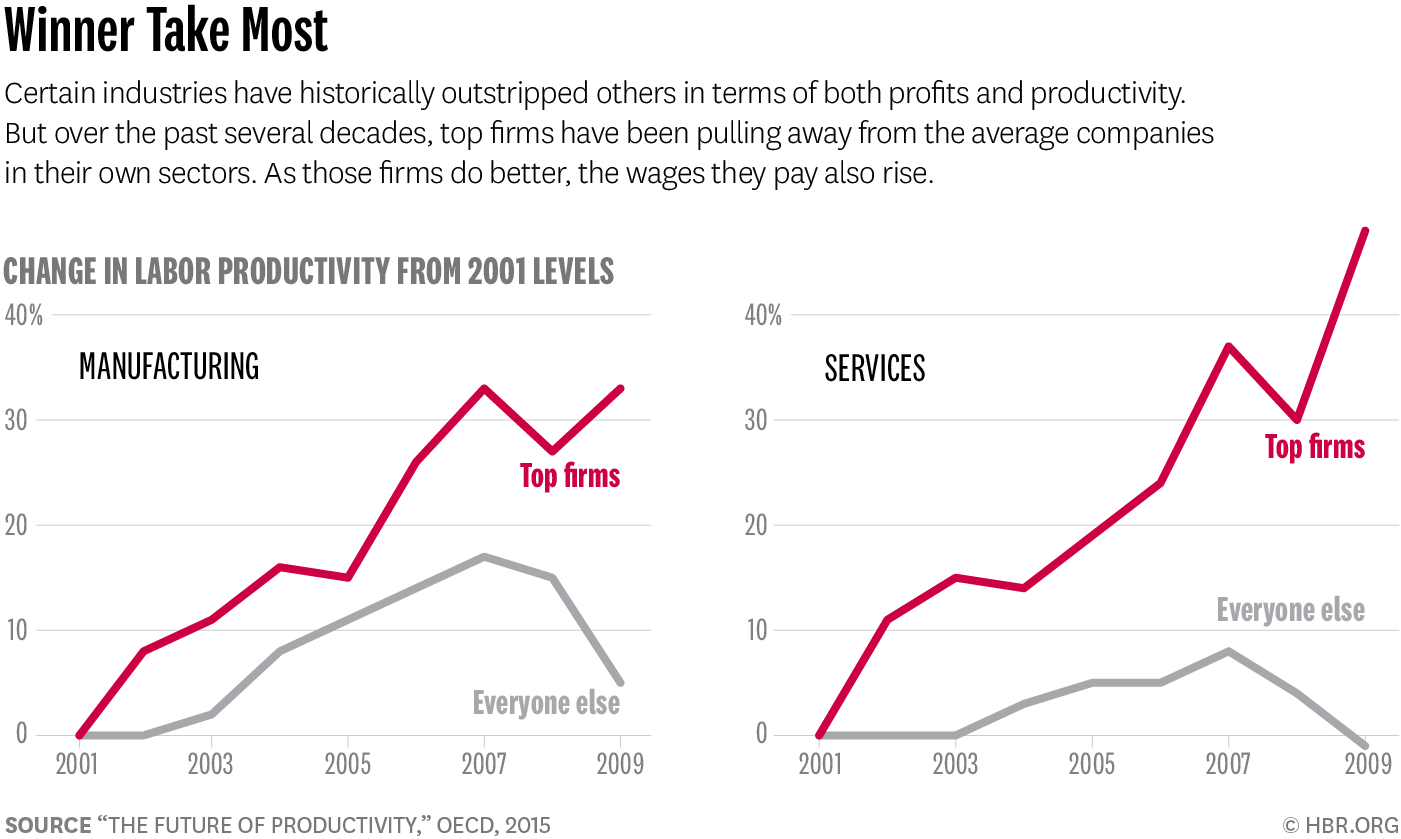

I’ve made this point over the years but it is worth repeating again. There are only two ways for an economy to grow. … One way is that the workforce increases, and the other is that you increase productivity. … Further, it is really hard to increase productivity in much of the service sector. How much more productive can a bartender or a cashier be? Or a taxi driver? Yes, we can eliminate their jobs with technology, but that just reduces the workforce side of the equation. … I don’t see us turning the workforce situation around unless we somehow manage to transform our negative imagery about immigrants and start to aggressively seek out productive young, educated immigrants from around the world.

Source: Men Without Work | Thoughts from the Frontline Investment Newsletter | Mauldin Economics

I have been promising a review of Nicholas Eberstadt’s very important book, Men Without Work: America’s Invisible Crisis.

…

At its heart, the book is about the fact that there are some 10 million American men of prime working age (25 to 54) who have simply dropped out of the workforce, and the great majority of them have not only dropped out of the workforce, they have also dropped out from any commitments or responsibilities to society. It is not just the labor force they are not participating in; they are not participating in the normal ebb and flow of community life.

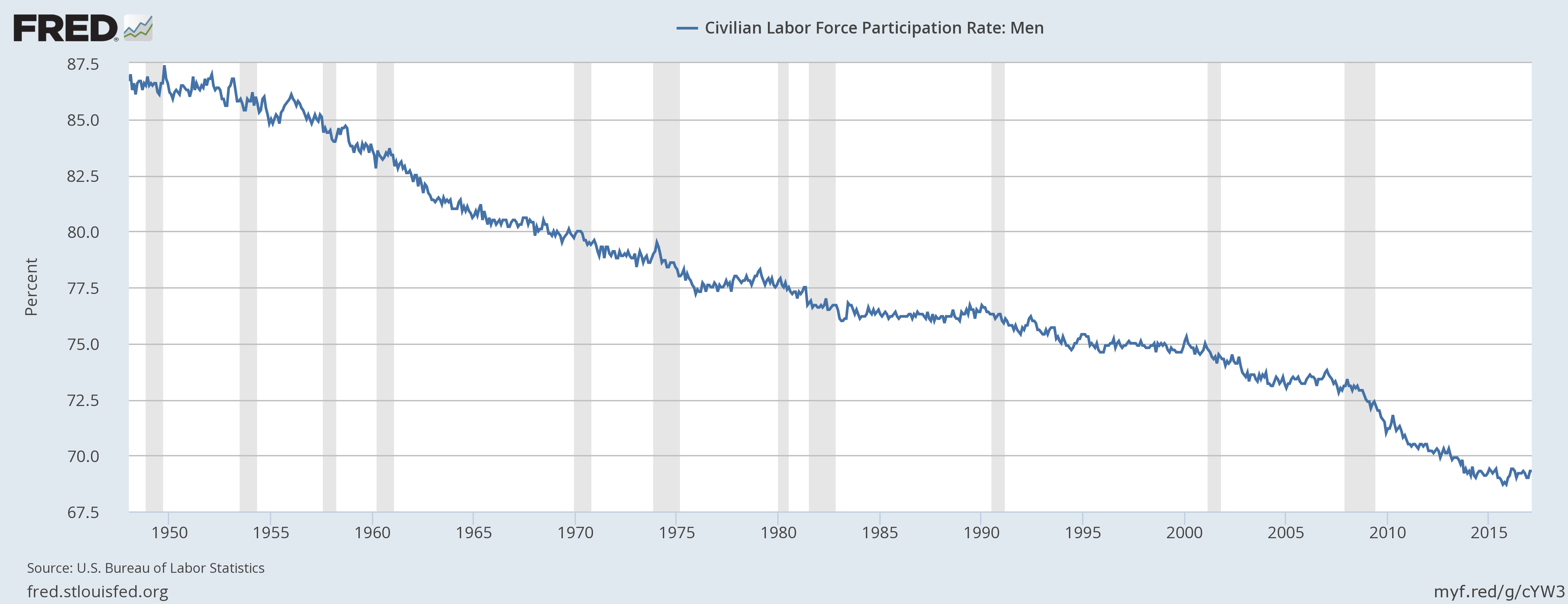

This is not a recent phenomenon. … Male participation in the civilian labor force has been steadily dropping for 60 years, through boom and bust years, periods of inflation and deflation, Republican and Democratic administrations and congressional control; the trend seems to be relentless – except that it has been accelerating since 2009.

Source: Men Without Work | Thoughts from the Frontline Investment Newsletter | Mauldin Economics

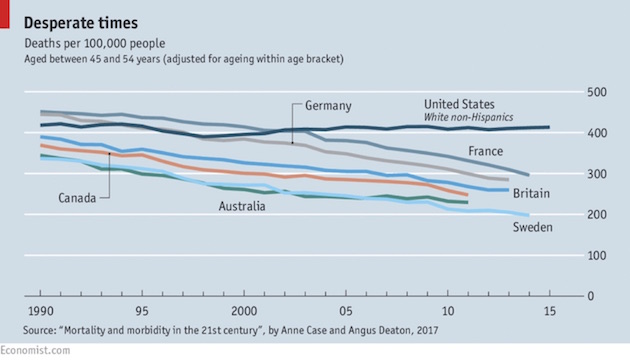

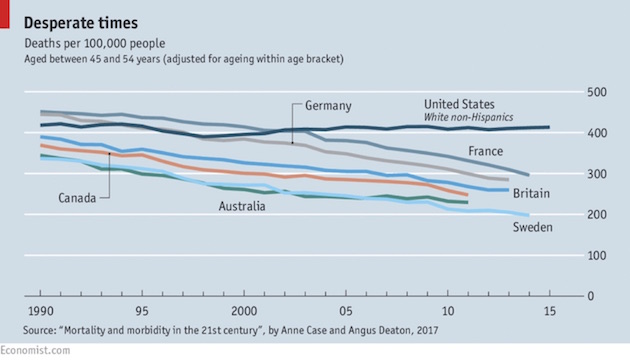

AMERICAN workers without college degrees have suffered financially for decades – as has been known for decades. More recent is the discovery that their woes might be deadly. In 2015 Anne Case and Angus Deaton, two (married) scholars, reported that in the 20 years to 1998, the mortality rate of middle-aged white Americans fell by about 2% a year. But between 1999 and 2013, deaths rose. The reversal was all the more striking because, in Europe, overall middle-age mortality continued to fall at the same 2% pace. By 2013 middle-aged white Americans were dying at twice the rate of similarly aged Swedes of all races (see chart). Suicide, drug overdoses and alcohol abuse were to blame.

Source: Free exchange: Economic shocks are more likely to be lethal in America | The Economist

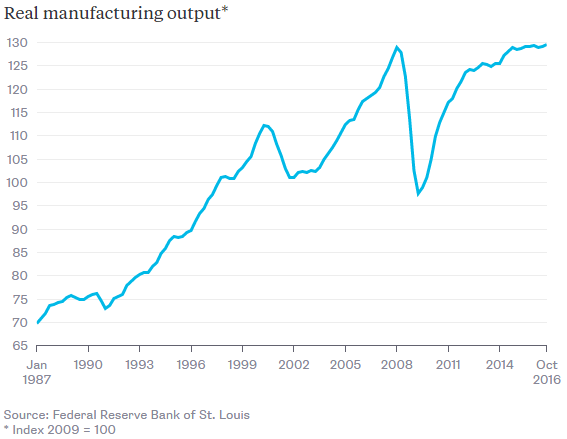

Job destruction caused by technology is not a futuristic concern. It is something we have been living with for two generations. A simple linear trend suggests that by mid century about ¼ of men in the US aged between 25 and 54 will not be working at any moment. I think this is likely to be a substantial underestimate unless something is done for a number of reasons.

I think this is likely to be a substantial underestimate unless something is done for a number of reasons. First, everything we hear and see regarding technology suggests the rate of destruction will pick up. Think of the elimination of drivers, and those who work behind cash registers. Second, the gains in average education and health of the workforce over the last 50 years are unlikely to be repeated. Third, to the extent that non-work is contagious, it is likely to grow exponentially rather than at a linear rate. Fourth, declining marriage rates are likely to raise rates of labor force withdrawal given that non-work is much more common for unmarried than married men.

On the basis of these factors I would expect that more than one third of all men in the US between 25 and 54 will be out of work at mid-century. Very likely more than half of men will experience at least a year of non-work out of every five. This would be in the range of the rate of non-work from high school dropouts and exceed the rate of non-work for African-Americans today.

Source: Men without work | Larry Summers blog

Source: Men not at work: Lawrence Summers on America’s hidden unemployment | Financial Times

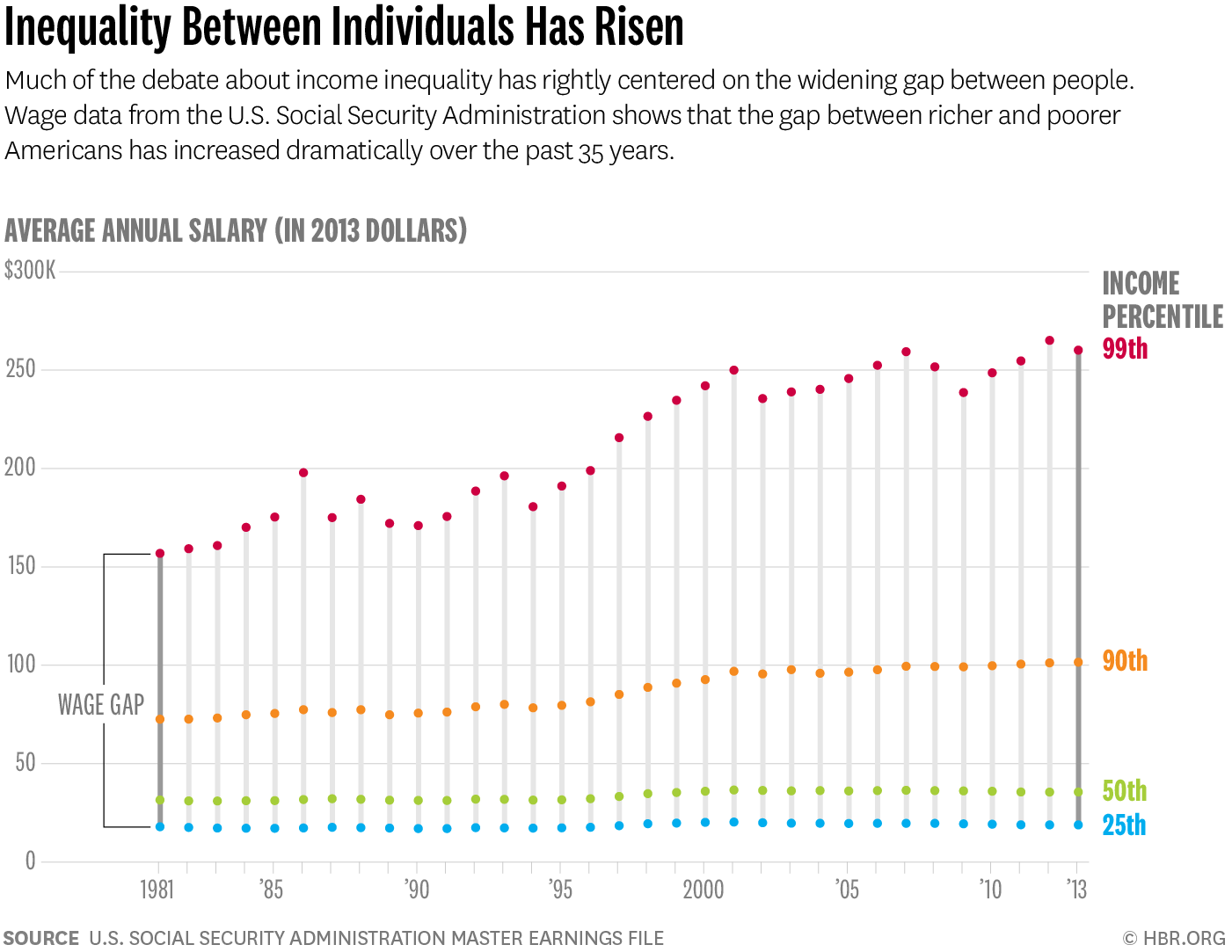

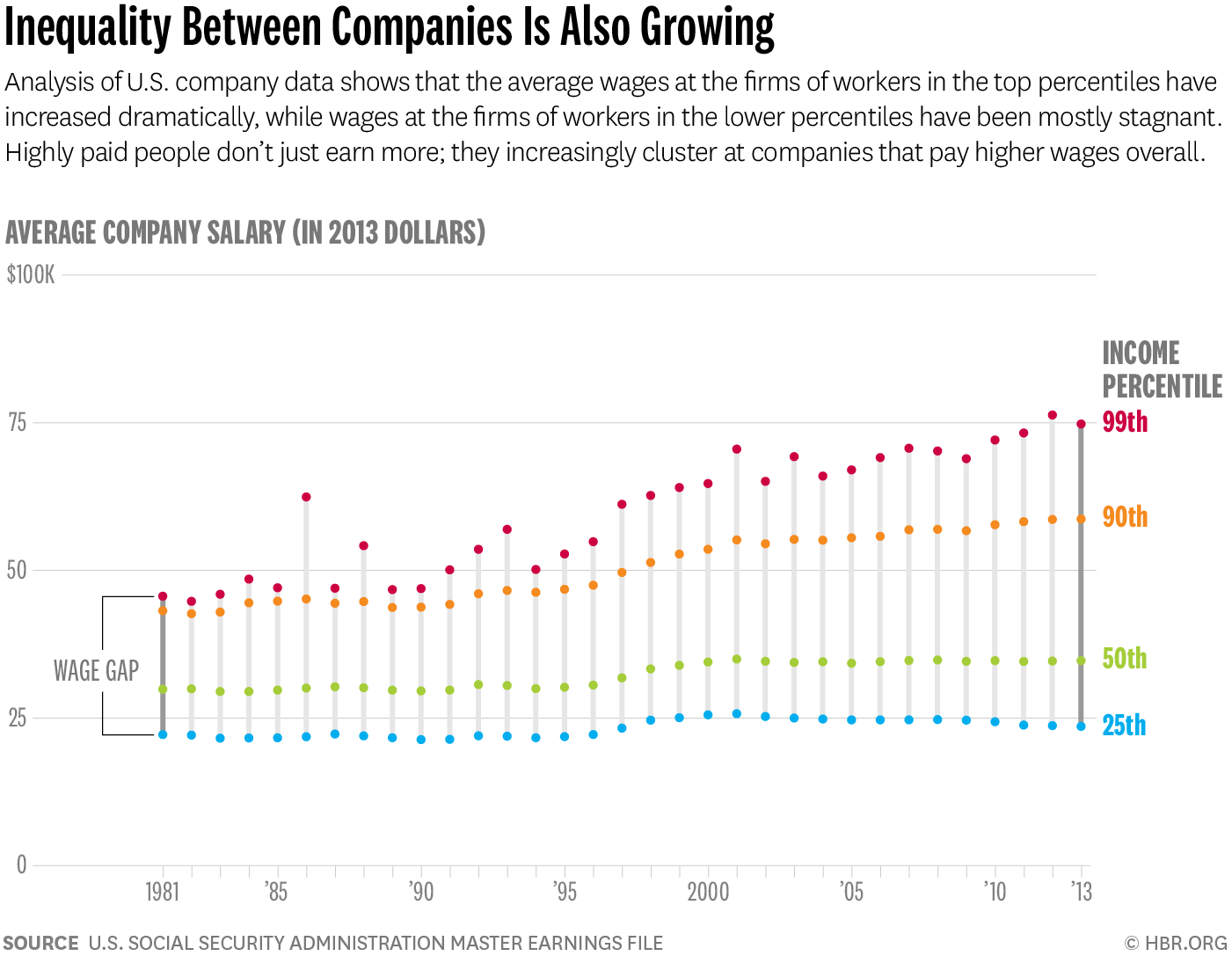

the progressive detachment of so many adult American men from the reality and routines of regular paid labor poses a threat to our nation’s future prosperity. It can only result in lower living standards, greater economic disparities, and slower economic growth than we might otherwise expect.

Between 1948 and 2015, the work rate for U.S. men twenty and older fell from 85.8 percent to 68.2 percent.

It is not just that LFPRs (Labor Force Participation Rate) have deteriorated for certain age groups or specific periods. Rather, the process has progressively depressed every successive rising cohort’s LFPRs over the course of the prime working ages….

In sum, an American man ages twenty-five-to-fifty-four was more likely to be an un-worker in 2015 if he (1) had no more than a high school diploma; (2) was not married and had no children or children who lived elsewhere; (3) was not an immigrant; or (4) was African American….

a single variable – having a criminal record – is a key missing piece in explaining why work rates and LFPRs have collapsed much more dramatically in America than other affluent Western societies over the past two generations. This single variable also helps explain why the collapse has been so much greater for American men than women and why it has been so much more dramatic for African American men and men with low educational attainment than for other prime-age men in the United States.

Source: Men Without Work: America’s Invisible Crisis by Nicholas Eberstadt